Black Businesses and the Generational Wealth Gap

According to a 2014 survey by YouGov, 64% of White Americans believed that past discrimination against Black Americans was a “minor factor” or “no factor at all” in explaining lower wealth levels for Blacks today. Of Blacks surveyed, only 34% agreed with that assessment.

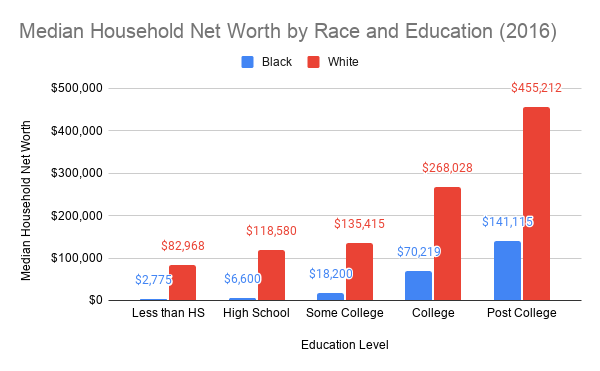

In just six years, attitudes seem to be changing with many Black and White Americans standing side by side to press for an end to systemic racism. Although we have seen more Black Americans attend college, gain middle class incomes, start businesses, and buy homes, a stubborn wealth gap persists between the two groups.

“This inequality holds back Black entrepreneurs and hurts our economy as a whole. It demands our attention. But we cannot fix a problem unless we identify the root causes.

”

The North Carolina Business Council firmly believes that when equal opportunity is extended to all Americans that it lifts all boats and creates a more stable and prosperous economy for us all. History tells us that the opportunities for business ownership and wealth creation were not equal, and that this inequality continues to deny us the jobs and wealth that Black-owned businesses could bring into our communities.

With Covid-19 widening inequalities, now is the time to empower Black entrepreneurs to change our future.

Black-Owned Businesses Benefit the Economy

Business ownership is a major driver of wealth for Black Americans. Black business owners have 12 times the wealth compared to non-business owning Blacks. Yet, as of 2017, as Blacks made up 13% of the population, only 3.5% of US-based businesses were Black-owned. Meanwhile, 81% of businesses that year were owned by Whites as they made up just 60% of the population. Expanding the opportunity for business ownership is critical for 40 million Black Americans and our economy at large.

Data proves that an increase in Black-owned companies contributes wealth to the US economy. The 2012 Survey of Business Owners by the Census reported that existing Black businesses contributed 1 million jobs and injected $165 billion in revenue into the US economy.

There is both hope and caution: Black businesses grew by 34% between 2007 and 2012. But the pandemic has affected Black businesses disproportionately, with 41% of Black businesses closing between February and April of this year while only 17% of White-owned businesses faced the same fate.

Access to capital plays a pivotal role in the divide between Black and White-owned businesses. According to a 2016 Stanford study comparing Black and White startups, Black-owned startups have 60% less capital investment than White-owned startups, and Black entrepreneurs in the 75th percentile of creditworthiness are twice as likely to not apply for a loan compared to White entrepreneurs with similar credit scores for fear of being rejected.

Two Separate and Unequal Economies

The disparity between Black and White business ownership has many causes. But a path to affordable home ownership plays the biggest part. For White families, this path was smoothed. During the Civil War, the 1862 Homestead Act promised land at a discounted price to White heads of household. Promisingly, it was revised in 1866 to allow Black Americans to acquire their federally guaranteed 160 acres. When land was denied them in the South, many Black Americans persevered, traveling to the Great Plains to claim their acreage on rough and tumble land in Kansas, Colorado, and Oklahoma.

While Black Americans worked to take their place in the US economy during Reconstruction, Jim Crow policies grew in the South in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These racist policies began to filter into the lives of Black Americans throughout the US as lawmakers of different regions worked to compromise with one another. It set the stage for federal policies of the New Deal and Post World War II era that would cleave a wide gulf between White and Black Americans—separating their lives into two separate economies with vastly different rules.

In the 1930s, the federal government enacted pivotal laws that benefited White Americans and harmed Black Americans. Housing segregation and the accompanying lack of access to conventional mortgages and banking opportunities has had the most lasting effect. In sum, these policies have denied Black Americans the opportunity to build generational wealth and relegated almost 20 million Americans (1960 Census) into a secondary role in the US economy.

Homeownership: The American Dream

Homeownership is now a lynchpin of the American Dream. But for many years it was out of reach for both Whites and Blacks. 50% down payments, short term mortgage terms, and high interest rates formed barriers to homeownership. From 1890 through 1940, homeownership rates hovered below 50%. But with the help of the Federal Housing Act and the GI Bill, the dream of homeownership would become a reality for a growing number of lower and middle class households. With 10% down payments, 30-year mortgages, lower interest rates, the stage was set for Americans to scoop up homes in the Post World War II housing boom.

But for most Black Americans, little would change and the opportunity to buy an affordable home still stayed out of reach. This intervention from the federal government helped to propel homeownership rates as they continued to climb steadily to reach 70% in 2002. But the path for homeownership was much different for Black Americans.

Source: Center for American Progress

Redlining is Born

Perhaps the most significant event in creating the wealth gap was the creation of the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) in 1933. In his 2017 book, “The Color of Law,” Richard Rothstein tells the story of the HOLC’s role in widening housing segregation.

With a housing shortage in the Great Depression due to foreclosures, frequently caused by high risk mortgages of the time, the HOLC, a federally sponsored agency, sought to expand access to affordable homes and help current homeowners refinance.

But before the federal government would back mortgages, they wanted to determine the risk of default. A neighborhood was deemed a safe risk if it was: “new, homogeneous, and in demand in good times and bad.” The HOLC drew maps to subdivide neighborhoods across the US. Neighborhoods with red lines drawn around them were deemed poor risks and would not be eligible for FHA loans. These were the neighborhoods primarily populated by Black Americans. Private financial institutions, such as banks and savings and loans, adopted the underwriting guidelines of the HOLC. “Redlining,” or federally-sponsored housing segregation, was born.

Although Black Americans were eligible by law to apply for government-backed loans, banks were free to deny them on the basis of the HOLC maps that deemed their neighborhoods a poor risk.

Many players enacted and perpetuated housing segregation. After World War II, an acute housing shortage led to a large boom in construction leading to a population explosion in the suburbs. Across the nation, in places like Levittown, New York and Milpitas, California, the federal government subsidized the building of new housing developments with the stipulation that no Black Americans be able to buy a home in the neighborhood. And to make sure it stuck, language was written into deeds saying that even when those homes were later resold that the rule still stood. Neighborhood covenants throughout the country solidified segregation by specifying that only “Caucasian” home buyers were eligible to live in the neighborhood.

When new homes for Black families or integrated neighborhoods were proposed by developers, the FHA turned them down, and local officials and citizens found ways to use the legal system to stop them from building. Frequently, the reason for objecting rested on the HOLC’s contention that Black homeowners depressed home prices, even though no data backed this up. In fact, when Black homeowners succeeded in buying a home, they often paid more for the privilege and had to be wealthier than their White neighbors to face the steeper loan costs.

While the boom in homeownership took off, the FHA and VA were insuring 50% of new mortgages. Yet during the years between 1934 and 1968, only 2% of the mortgages issued by the FHA went to minority homeowners.

Source: Center for American Progress

As White homeowners grew their wealth through rising home equity, Black families faced a choice. For those with the means, they could persist in trying to buy in White neighborhoods where amenities were concentrated, or buy in Black neighborhoods, where, due to zoning rules, redlining, and a lack of investment, their home purchases were less likely to earn them a return.

For Black families who did manage to buy homes in White neighborhoods, they faced a swift backlash. The judicial system largely turned a blind eye to discriminatory racial covenants. White homeowners lashed out, and with the help of law enforcement, pushed families out of the homes they had legally bought.

A lack of access to banks formed another barrier to wealth. For Black homeowners, regardless of the neighborhood, the cost of purchasing a home was much steeper. With little access to FHA and VA-backed loans because of the banks’ allegiance to the redlined HOLC maps, Black households were forced to buy homes through contract sales, a process that was more similar to the pre-1930s housing market. Buyers faced a long road to building equity because, unlike the amortized FHA loans, buyers paid interest-only payments, frequently for 15 to 20 years. Missing one payment during this period could result in the loss of your home.

While waiting to build equity, many families were forced to stay in homes even after the neighborhoods had deteriorated due to a lack of investment and zoning changes. Meanwhile White suburbs, zoned for single family homes, grew in value. Black neighborhoods were often zoned so that junkyards, factories, and chemical plants abutted residential homes, and homeowners found their values plummeting. This led to these neighborhoods being considered an even poorer risk for insuring mortgages.

By 1968, when the Federal Housing Act was rewritten to “prohibit discrimination concerning the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, or sex,” the damage had been done. The law could not reverse the advantages gained by White Americans in the over 20 years since the end of World War II. While White families gained equity from the purchase of federally subsidized homes, these same homes were now out of the reach of the average Black family.

Even with housing discrimination outlawed, it was hard to enforce. In the next decade, new laws were passed to give the revised Federal Housing Act teeth. Banks often refused to abide by the regulations and overt housing discrimination persisted through the 1980s.

Prosperity Denied

Had the Federal Housing Act, the GI Bill, and job-related laws provided equal opportunity for Black Americans, our economy today would have the benefit of generations of Black Americans with generational wealth that could support business ownership. But as the federal government and private institutions such as banks and colleges failed a large portion of Americans, we now face an unequal playing field for Black entrepreneurs.

In 1989, of the 6% of Black households who received family inheritances, the average amount was $42,000. White households, with 24% of white households inheriting family wealth, received an average of $145,000.

Against this backdrop, Black business owners, regardless of their education and experience, face fear when applying for a loan or credit. With a long history of banks denying loans, Black entrepreneurs face a higher likelihood of being denied a loan even when comparing amongst similar education, creditworthiness, and experience.

According to a 2016 Stanford study comparing Black and White start ups, White-owned start ups begin with an average of $106,720 in capital while Black-owned startups originate with an average of $35,205, and never catch up. At the outset, White business owners borrow six times as much as Black business owners. Even when accounting for education, experience, and above-median credit scores, Black entrepreneurs are less likely to apply for a loan.

Expanding Opportunities

With a growing number of Americans demanding an end to systemic racism, this is the time to seize change. Although we cannot alter the past, we must acknowledge it and work together to amend inequalities.

The North Carolina Business Council is committed to expanding opportunities for Black entrepreneurs. We know that it will take changing minds and institutions.

Among investors and bank loan officers, there are misperceptions about capital investment in minority and women-owned businesses. A 2018 Morgan Stanley report found that 80% of investors and 88% of bank loan officers said that “multicultural and women business owners get the right amount, or more, of the capital they deserve to run and grow their businesses.”

In reality, Morgan Stanley estimates minority and women-owned businesses face a $1 trillion funding gap. Bridging this gap will not only provide expanded opportunities for entrepreneurs, but will grow our economy as a whole.

References:

“The Color of Law” by Richard Rothstein (2017)